In his “Liturgy for Embracing Both Joy & Sorrow,” author Douglas McKelvey writes:

“In one hand I grasp the burden of my grief,

while with the other I reach

for the hope of grief’s redemption.”

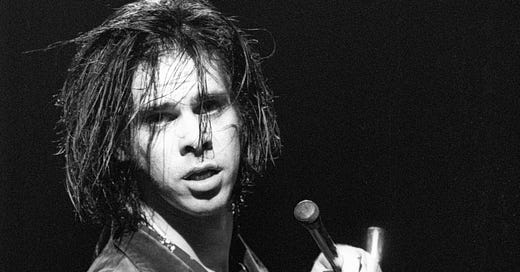

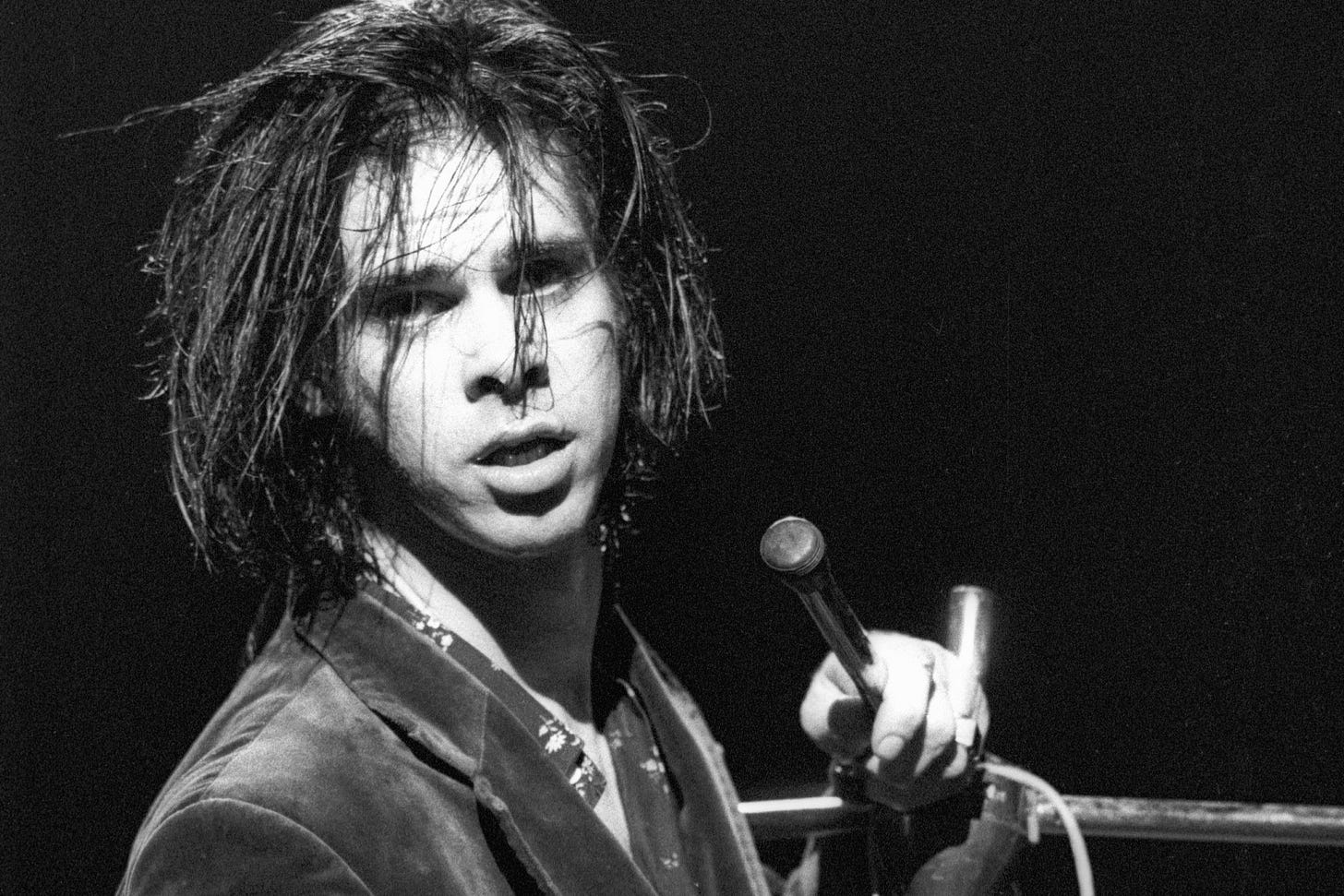

I’ve been thinking about that phrase at the beginning of this Lenten season, as it clearly reminds me of the music of Nick Cave, whose 40-year-career has always existed in the tension between joy and sorrow, grief’s burden and redemption. So this lent, I’m meditating on Cave’s discography, and I’d love to invite you along.

Last month, I offered a brief discussion on murder ballads—their historical context, the 20th-century feminist rebuttal, and the idea that the presentation of dark realities in art is separate from the promotion of those realities. In that essay, I defended the expressions of artists like The Chicks, Carrie Underwood, and Miranda Lambert who attempt to expose a violent tradition within country music with songs like “Goodbye Earl,” “Two Black Cadillacs,” and “Gunpowder & Lead,” respectively.

But I’ve wrestled with how to feel about murder ballads from the male perspective, without the subversive context of the songs I’ve just mentioned. It seems more often than not that, at least in semi-recent history, popular murder ballads are either ambivalent or empathetic toward the song’s violent perpetrator. Take Jimi Hendrix’s 1966 rendition of “Hey Joe.” The titular character shoots down his old lady for messing around with another man. He then goes way down south to Mexico where he can be free of the hangman’s rope. No judgment is made lyrically nor musically. In fact, the lyric is adorned by Hendrix’s explosive mastery of the guitar, leaving the listener energized and awed by the rock star despite the dark themes.

I admit, this makes me uncomfortable. While trying to discern what a proper expression of the murder ballad genre would sound like (because this certainly didn’t seem to be it), I turned on Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ 1986 album, Kicking Against the Pricks. Here, Cave and co. cover a handful of songs by his influences—from The Velvet Underground to John Lee Hooker to Lefty Frizzell. Coincidentally, many of these songs are murder ballads. And I love them.

So what’s different? Well, first, Nick Cave has one of the stronger moral compasses in modern music. He understands ideas like justice, mercy, grief, and hope in a way that has helped me process those difficult topics immensely (more on this in subsequent essays). So, when Cave turns to violence and perversion, I listen closely. And what I’ve noticed in his treatment of murder ballads on Kicking Against the Pricks and elsewhere is that Cave doesn’t just tell the story of a crime; instead, he becomes the villain, vile and profane.

For some reason, playing the villain through music isn’t something that’s easily embraced, though it’s commonplace in other art forms. I’m reminded of C.S. Lewis giving voice to the demonic in The Screwtape Letters, or any actor ever whose portrayal of an on-screen villain was never a reflection of the artist’s own morality. However, when set to a melody, we cringe to hear the vile, the profane, and the violent. Cave doesn’t care. Listening to his music—especially his early music—you have no choice but to take a hard look at humanity’s depravity and reckon with it.

On Kicking Against the Pricks, Cave also performs “Hey Joe,” offering a different conclusion than Hendrix. Again, Hendrix’s rendition borders triumphant with soaring blues solos. Justice isn’t served, and the listener is left with a guitar hero rather than a violent villain. But when Cave and the Bad Seeds perform “Hey Joe,” there’s no mistaking the darkness or the justice. Mick Harvey’s death-march drums and pounding piano, Hugo Race’s scraping guitar, and the steady foreboding of Tracy Pew’s bass set an eerie gallows scene. And when Cave finally resolves in his baritone drawl, “No hangman’s about to put a noose around me,” it sounds less like a victorious escapee, more like the final words of a delusional convict as the trapdoor drops.

Cave offers us an opportunity to contemplate human evil—not to feel woe for the broken world or to gain some sort of self-righteous sense that there are people worse off than you. In a Red Hand File about evil (Cave’s series of letters answering fan questions), Cave writes,

It requires little self-examination to envisage a situation where ‘good’ people could—under certain circumstances—perform acts that are wicked. This acknowledgement of our own capacity for evil, difficult as it may be, can ultimately become our redemption.

This explains the proper context of the murder ballad genre or other modes in which the musician takes on a villainous role. In presenting the vileness of human nature to the listener, Cave asks us to respond and reflect on our own wickedness and need for redemption and to consider how we can move toward championing justice and mercy in our own lives.

In the next Quarter Notes, I’ll explore those subjects as Nick Cave comes to “The Mercy Seat.”